Curated by Tiago Sant’Ana

The Buriti is a plant from the palm family whose leaves spread out in long raffias and sweet fruits pop in clusters that fall from long stems. Wherever you see a buriti, there is water nearby, as they are a kind of oasis indicator, because it’s in the middle of swampy, marshy landscapes that the tall palm tree takes root and grows. The buriti is the symbol of a certain place: The Cerrado biome, which spreads out across much of the center of Brazil, including the west region of Bahia. It’s also through the cultivation of this species that a lot of subsistence farmers make their living, by selling to several distinct chains of production of the fruit, the leafs and the hearts of palm from the Buriti.

***

Right in front of a Buriti tree, a woman gazes at the spectator, surrounded by a bowl full of the fruit from the plant. She carries with her dresses with celestial colors intercalated with pieces jaguar skin. From her neck, falls a kind of scarf, turned back onto her shoulder. Her clothing, in cerulean tones, seems to be armor. Her physical position follows the same verticalized direction of the buritizeiro – as if her feet on the ground get lost within the roots of the plant themselves. Around her, it’s possible to see a machine used in huge agricultural harvest and an airplane that expels poison from its tanks. On the top of the canvas, a Pokémon exhales a toxic gas and wears a cowboy hat, very common in the Brazilian agribusiness culture.

This description is from the painting O último buritizeiro by the artist Felipe Rezende. This same title lends its name to the exhibition presented by Rezende at Galeria Leme, and provokes us to reflect on a scenario in which survival and subsistence dynamics are caught in a complex conflict with machines and the relentless advance of ecosystem destruction – in which humanity itself is inserted.

The woman that appears in the painting is Domingas Guedes, known in the Cacimbinha community as Ozelina. Dona Ozelina, like many other people in this region located on the West of Bahia, is descended from the indigenous and the quilombola people that found in this geography a place abundant in water and other natural resources hidden by the geographical isolation allowed by the cerrado. This area has suffered a series of threats by private companies and by the agribusiness, whose activities are also contributing to the poisoning of ground and water.

The painting by Rezende cited previously, in this way, brings the nature and native people to the center, cornered people by a sort of threat – as a spacial analogy of what is happening in this region of Brazil. Far from being a purely denouncing character, however, the artist creates this narrative using a pictorial discipline and a very particular visual vividness. Not just because of the accurate uses of oil paint and its properties, but also overlapping figures from different traditions and starting points, like the insertion of anime culture and also resorting to the poetry of the full body portrait – sacralized language inside occidental art as a way to represent important characters of a specific social context.

In this way, the turning point brought about by the artist is conjugated through an own visual intelligence element that will contribute in the incubation of an almost delirant imagetic repertory that works as tools for the construction of a diegesis ruled by social and class struggles.

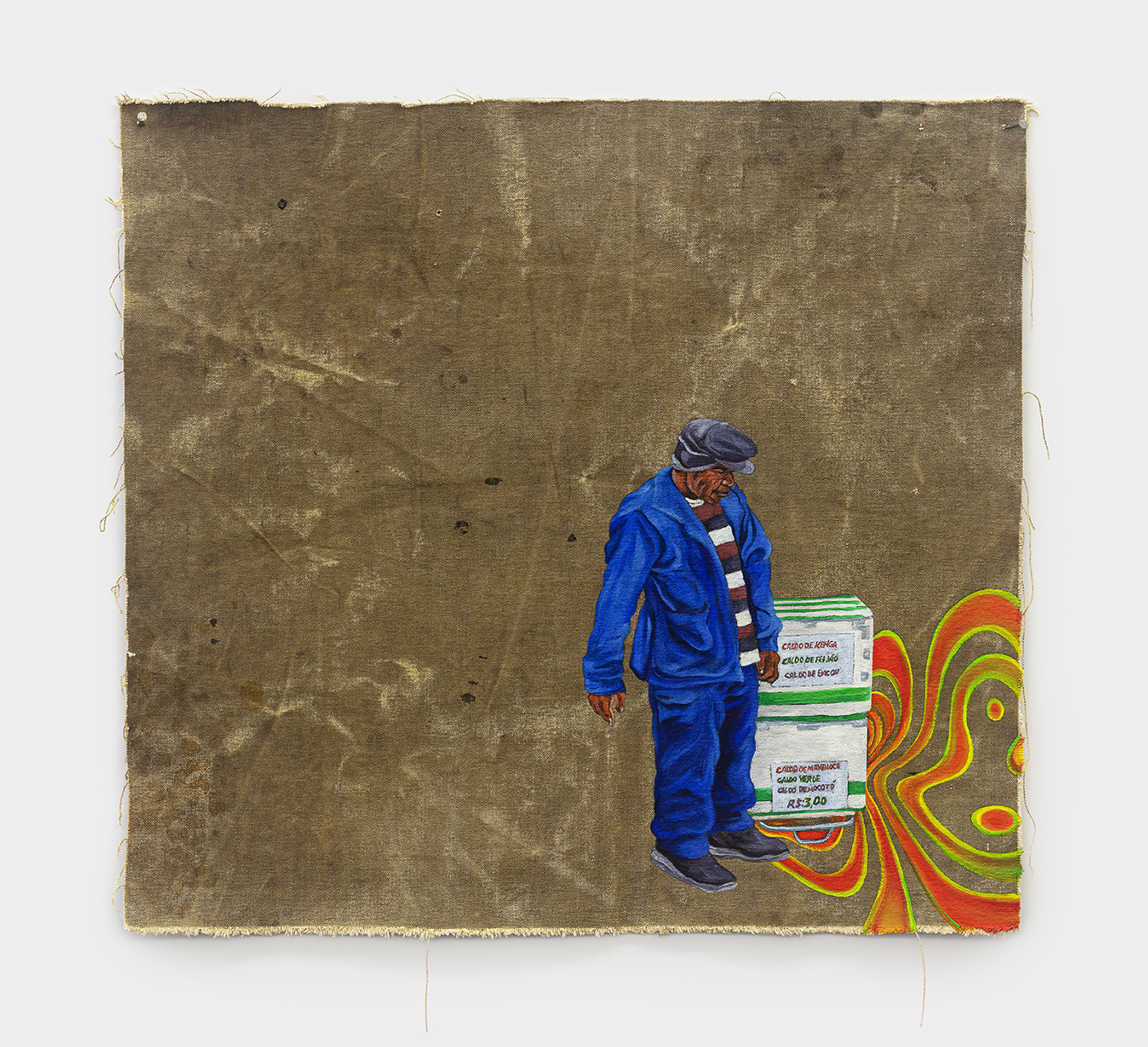

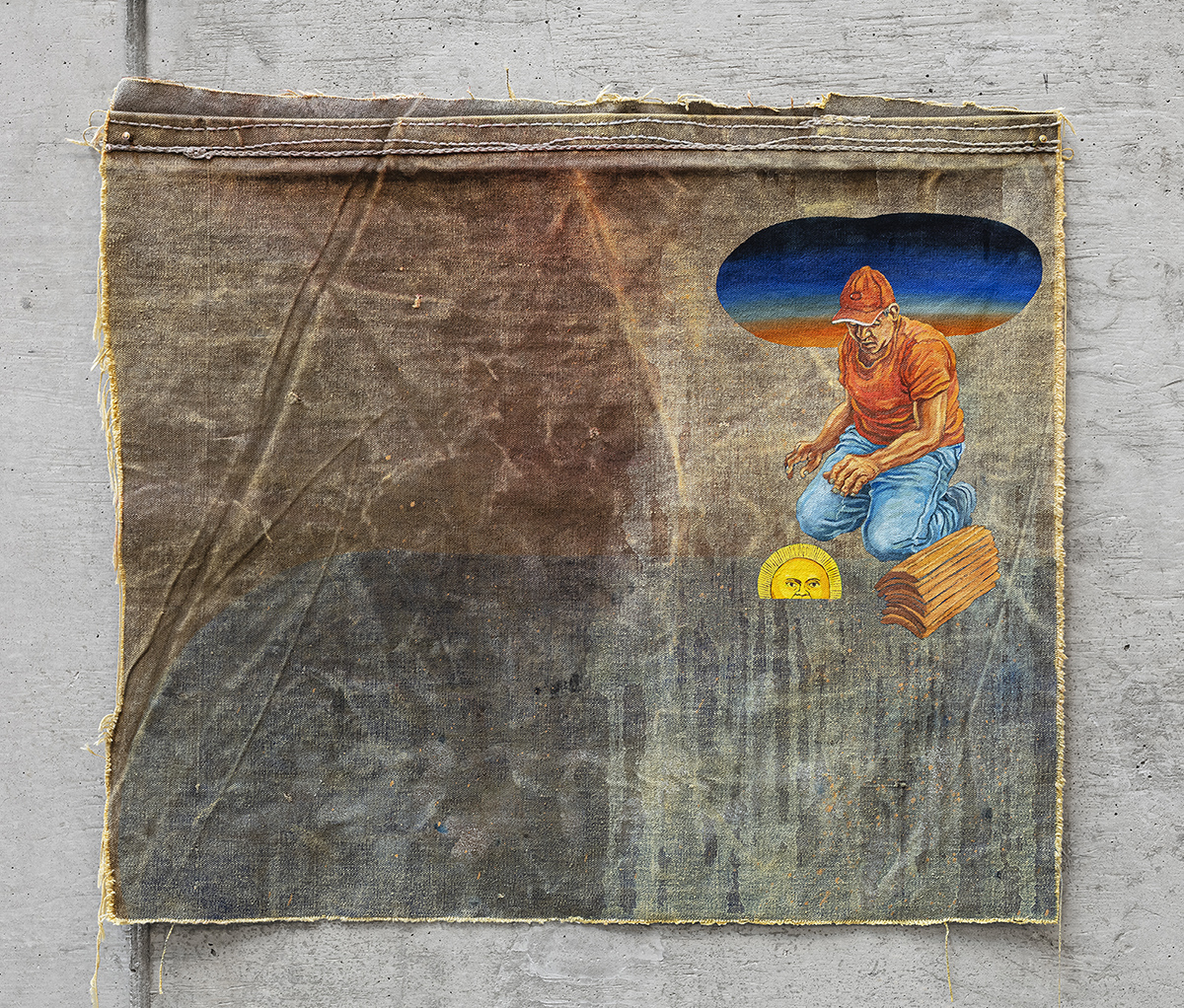

Felipe Rezende uses the truck tarpaulin as a support for his paintings. And this material preference isn’t just an aesthetic choice. The tarpaulin travels, moves physically through roads and these traffic marks are impregnated in its fibers. Patches, lines, stains, footprints can be noted when we look more carefully at the support used and they certify temporal and geographical changes of the material. Therefore, the elected support by Rezende is a metaphor throughout which we can reflect on the fluxes of the figures that protagonize his paintings.

The course of the exhibition O último buritizeiro leaves the last affirmation apparent. If Dona Ozelina appears imponent right in front of a buriti, in the piece Semearam cinzas pra colhermos fósseis [They sowed the ashes for us to gather fossils] we can see a couple that rests over burned ground. The dark portion at the bottom of the painting is interrupted by two human figures: one resting over two construction blocks and the other making a movement as if she is almost rising up, but if she did that she would be threatened because she would fall in a dark hole under her feet. On the top of the canvas, the skeleton of an undefined figure seems to have come out from an archaeological site. Here, Rezende talks about a duality between the life and death drive. At the same time that we see devastated ground, it’s over the building blocks that the woman rests – as an attempt to articulate that, despite everything, it’s possible to construct a new life. Perhaps in another time, maybe in another place, because the scorched earth is an impoverished earth, burned, poisoned, buried within which the dream that a seed will sprout again.

It’s on attempting a better horizon that conducts us to another canvas present in the show. O vendedor de caldos e o moedor de carne [The broth seller and the meat grinder] is presented as a kind of header, where we observe an almost apocalyptic sky, with an atmosphere overtaken by a dense daub of pollution. Under it a man puts himself in a fighting position facing paraphernalia which brings with it on its way out, a meat grinder. On this machine, in low relief, its written “São Paulo”.

Fighting against a machine that grinds people is the reality of many people who left their hometown and went to the biggest Brazilian metropolis. It’s through the resulting mass of the milling of these people and their dreams that the pillars of this society are made. On the opposite bottom part of the piece, a recyclable material collector woman waits for the result of the clash between human x machine so the residue of this fight can be collected and reinserted into the production system.

The course that Felipe Rezende shows to us in the exhibition O último buritizeiro is a glance at the earth and nature as spaces of conflict, but it also brings near the stories of many people’s flight from their earth scorched by capital ambition in the pursuit of other possibilities of living, of escape zones. This flow of comings and goings gets confused with the life of the artist himself – who has been living in transit between Salvador, his hometown, Barreiras, in the Bahian west, and São Paulo, where he has been currently working.

***

GuimarãesGuimarães Rosa was known for singing the buritis. The buriti, for him, was the symbol of Brazil itself. A deep Brazil that many people still don’t known. When there is only one buritizeiro left, its seed will fall on the soggy ground of the paths, that will bring forth more and still more palm trees, living up to what “buriti” means in tupi: natural of life. As long as one last buritizeiro lives, the Brazil sumg by Rosa lives, the Brazil of the paths, of people who plant their feet on the ground as if they were roots, just like Dona Ozelina in Cacimbinha.