The Madrid-based Peruvian artist, founder of the fictitious and virtual museum LiMac, will present at Galeria Leme “What Made us Modern / Crisp Images in a Humid Environment”, her fourth solo exhibition in São Paulo.

Given the current promise of modernization in Peru, to be understood as the real presence of the state in the country and therefore as a right to citizenship for each individual, this exhibition reflects on what happened in Peru during the first era of the uncompleted modernity and on what signified its posterior lack of concretization.

“An attempt to make crisp images in a humid environment” is how the sociologist Aníbal Quijano describes the impossibility to do vanguard poetry in Lima, which can also be extrapolated to the field of visual arts. The crisp images to which Quijano speaks of refer to machines, to the industry and to the new ideas that, in a city like Lima, without nearby industries and without technical development, were impossible to create and disseminate. This moist environment not only refers to the real humid climate of Lima but also to the “social humidity” that made it impossible for new images with clean margins and plane colors to emerge and settle in the collective imaginary. This humidity would be the product of the yet ongoing effervescence of an imposed nationalism, the vapors of a slowly cooked multiculturalism and the permanent oxidation of the social processes.

The historian Armando Alzamora described that time period (1916 – 1936), as such: “A certain way to think spaces began to emerge, like a sophisticated geometric mold on which hard blocks had to fit, some unusual, but all loaded with this new spirit. To that extent, this sort of avant garde mythology could only have developed in a paradoxical instance, not for its plurality, but more for its discursive character: the vanguard. It was in fact the exact medium, the perfect dimension to transpose the states of a changing world that on the other hand only existed within us as an absence.”

Local artists rejected the promises of Western modernity, and consciously returned to the recovery of the landscape and the Andean habitant that, seen from Lima, seemed as far away as the past, but closer than the metrópolis that was announced by the future. This movement, denominated as Indigenismo, had a modern perspective as it thematically opposed itself to European classicism while it utilized forms that maintained them on the fringes of what was done on the continent.

This recuperation of the Andean in the arts also reflected itself in other fields of study such as anthropology and archeology that renewed in a more integral version in which the distance between the object of study and the investigator was abolished. The integration process of the rural population had its climax during the Agrarian Reform of 1968 as it made them owners of their lands again for they had been worked by them for generations. However, as the state had not been capable to concretize its proper modernization, its unfulfilled promise became the breeding ground so that years later terrorists groups began to emerge in the country during the 1980´s and 90´s.

This violence was necessary, so that Peruvians began to see themselves as a multicultural and a plural society. The following phrase by the sociologist and philosopher Mirko Lauer “Violence made us moderns” therefore applies to a modernity that needed violence to carry on, a duo that has repeated itself at each attempt.

The works in this exhibition oppose, mix and force the modern imaginary, with the photographic registration of the violence of the 80´s, parting from what the Mexican caricaturist Marcius de Zayas mentioned regarding new photography or pure photography as an artistic discipline that surpasses all forms because it brings the plastic verification of the facts, a visual proof of what he called “material truths of the natural world.”

The exhibition of both imaginaries, reunites doubles such as modernity / violence, abstraction / realism, dryness / humidity, where none overlaps the other but on the contrary are forced to live together.

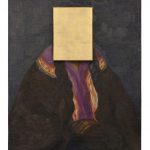

Utilizing the iconic “Homage to the Square” paintings by the artist Joseph Albers as a starting point, images of the terrorist violence of the 80´s in Peru has been included in an almost invisible manner. To reveal themselves, it is necessary to get close to the painting, a contrary movement to what modern paintings proposed. Similarly, the series that is named after the exhibition title, What Made us Moderns, consists of 10 paintings that creates a gradient of grey and have the exact same measurements of the concrete blocks of which the gallery is made of. In such a way, the works surrender themselves to the architecture and live with it in a fully modern act. If we look at them from far away, this gradient made out of a Kodak scale of grey coexists without friction with the architecture. But in each corner of the paused, measured and clinic monochromes, a set of pictures appear and break this transition. These images tell us about a constant that is of capital and latent permanence.

This exhibition also includes copies of indigenous paintings in contrast with the images that were created outside of Peru, as an attempt to find impossible relationships through the construction of pictures that never existed.

The videos entitled “Abstractions”, “Natural Landscape” and “Ashes to ashes” are three reflections on the delicate relation between the pre-Columbian heritage, the rural present and Western culture in the light of the promises of development and modernization.

About the artist:

Sandra Gamarra was born in Lima, Peru, in 1972. She lives and works in Madrid.

Her work has been featured in numerous exhibitions, including the shows Setting the Scene, Tate Modern, London, UK(2012); At the Same Time, Bass Museum of Art, Miami, USA(2011); XI Bienal de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador (2011); Fiction and Reality, MMOMA, Moscow, Russia (2011); Arte al Paso, Colleción Contemporanea del Museo Arte de Lima, Estação Pinacoteca, São Paulo, Brazil (2011); 29ª Bienal Internacional de São Paulo, Fundação Bienal, São Paulo, Brazil (2010); 53ª Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy (2009); . Her work is in private and public collections such as MUSAC, León, Spain; MoMA, New York, USA and Tate Modern, London, UK.