Sympoeitics

Ana Avelar

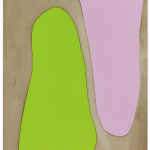

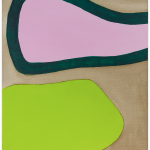

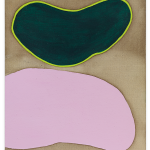

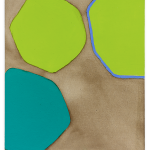

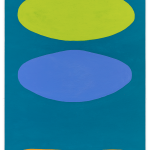

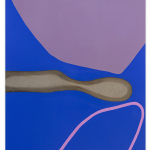

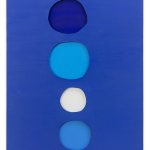

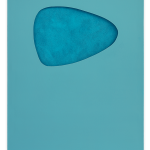

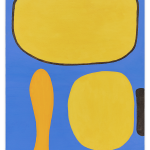

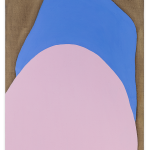

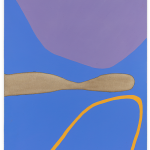

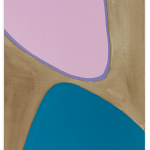

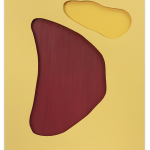

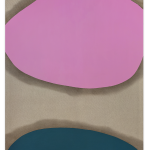

Germana Monte-Mór’s recent works operate with forms that hover on the brink of encounters. Fluid oval figures represent continents and islands separated by rivers and seas, droplets of oil meet in aquatic environments, cells and bacteria draw nearer. The world is silent, and yet it is always in motion.

In the early 20th century, European artists began exploring abstract forms, drawing inspiration from nature as a fundamental reference. This pursuit was closely linked to the advancement of scientific discourse, with the aim of developing a personal yet universal visual language capable of being understood by a wide variety of art viewers or art interactors. Leading figures in this bold artistic undertaking included Kandinsky, Delaunay, Hilma af Klint, Klee, and others.

German researcher Linn Burchert argues that abstract art, conceived in this way, sought to represent natural phenomena not through direct depiction, but by addressing the psychological and physical effects of color and form – effects analogous to those experienced in the natural world. In this sense, abstractions were not derived from visible objects and translated into non-figurative images; rather, they represented non-visual, albeit perceptible, aspects of reality, which, though they exist in the world, and are thus “real”, lacked a visually presentable form.

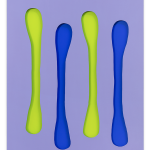

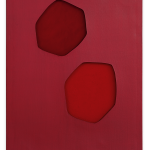

From this standpoint, color was absolutely central to Kandinsky, Klee, and especially Johannes Itten, who saw artistic creation as a way to “create life.” As Burchert notes, rhythm and movement, along with chromatic qualities, were key to Itten’s concept of the “vitalizing image”, where movement is regarded as a precondition of life . Similarly, Monte-Mór uses color in a strategic manner, exploring the relationships between hues and tones, a subject the artist investigated and experimented with in her notebooks. Oil-paint blues and greens meet pinks; cooler colors are set against warmer ones, and reds emerge in various shades and gradients (asphalt, which featured prominently her earlier works, has been relegated to a secondary role). Some colors are confined to certain areas of the composition, while others seem to spill beyond the plane of the medium, as if they were spreading out across the walls and dripping onto the floor.

Just as color was used for its “spiritual” connotations – that is, its effects on human experience – graphic forms of communication from earlier periods also inspired abstract artists. Prehistoric inscriptions, among other forms of expressions, served as key visual references, symbolizing a time when inner and outer human life were indissociable, shared collectively, and also served as privileged intermediaries of spiritual communion and communication.

Hans Arp favored the oval shape over the static circle as a central element in his poetics. This form, which is reminiscent of eggs, leaves, and pebbles, was for Arp a symbol of the human navel, torso, and head—a “symbol for metamorphosis and organic growth,” simultaneously expressing universality and change . Arp explored natural processes such as birth, growth, metamorphosis, and death. As German art historian Isabel Wünsche notes: “The multitude of possible realizations, combinations and arrangements symbolizes the continuous movement of nature from the microscopic to the orbits of the planets”.

Familiar with the debates surrounding Western abstract art history, Monte-Mór, a professor of drawing and color, develops a contemporary abstract vocabulary rooted in the lexicons of the avant-garde. However, given her unique historical and geographical context, her academic and self-directed training, and her embodied experience, the artist combines knowledge of painting, printmaking, drawing, and the histories of modern, contemporary, and so-called popular or folk arts with anthropological insights. Attentive to human behavior in its social, linguistic, and biological dimensions, her painterly and sculptural work – particularly her recent counter-reliefs, with their recesses and cuts revealing hidden layers – engages the senses of sight, touch, and color, while also delving into the long-term symbolic aspects that connect these signs and forms to human ancestries.

In the 1980s, critic Lucy Lippard, known for her critical feminist approach, embarked on a detailed study of prehistoric art. Seeking a reprieve from the contentious New York art scene, she found an “overlay” between her interest in ancient monuments and her commitment to contemporary art. By creating a collage of different eras and spaces, Lippard presented ideas and images that, while somewhat enigmatic, occupied similar places in our imaginations.

It is intriguing to consider how certain symbols like the spiral, the meander, the horizon line, and the oval span virtually all historical moments and cultures of humanity. Although, today, we may not fully grasp them in a rational sense, we still experience and connect with them on a profoundly intuitive level. As Lippard states, “the symbolic content of abstraction today is subterranean, inaccessible to the majority of its viewers” – hence, we need artists to articulate their meanings and significance , since we have lost confidence in our ability to interpret or even assimilate these symbols.

For the critic, human time and geological time overlap, as seen in Germana’s 2010 photo series, “Soft Stone,” where rocks balance on rocks or are juxtaposed on a riverbed—a similar composition to her 2008 Amber series. In many cultures, to this day, stone symbolizes the perennial, enduring existence of nature, in stark contrast to our fleeting mortality, while the image of a river evokes the ideas of transience and transformation.

In the reality of prehistoric times, humans and non-humans often collaborated in artistic creation, and making art was simply one of many human activities. It is crucial to acknowledge that, just as art in the past was part of the human experience in the past, its understanding was also shared among individuals. Today, so-called abstract art often seems esoteric or abstruse to many, and yet its content, contrary to what is popularly believed, is nonetheless relevant – evoking important concepts and ideas. Proximity and distance, weight and lightness, fluid and fixed, projection and recession – aspects present in Monte-Mór’s work – are notions that can be observed in nature and are accessible to one and all.

Monte-Mór’s work exists within a sympoiesis – to use Beth Dempster’s term, as cited by biologist and feminist theorist Donna Haraway – of forms and colors, where each and every element is essential, because the work emerges from cooperative relationship between organisms within an undefined collective system. “Information and control are distributed among components. The systems are evolutionary and have the potential for surprising change” . Sympoietic actions are inherently creative, whereas those who work in isolation tend to be predictable, even if efficient.

Lippard suggests that art likely emerged from the “perception of relationships between humans and the natural world” . As such, the connection between femininity and nature recurs in various mythologies, relating to the cycles of life and death – from Pachamama to Gaia, and even the Virgin Mary, the guardian of the living and the dead. Arp sought “symbols of metamorphosis and the development of bodies” , which he found in “fluid ovals,” a form that has always been deeply emblematic of life.

Thus, it can be said that Monte-Mór follows the principle of nature as the measure of all things, creating moments of imminence rooted in the relationship between bodies, where everything is in flux, transitory. Playing with oval shapes, she refers to her works as “fissures” and “holes.” As the artist explains, what drives her art is “the desire to reveal something that cannot be revealed.” In other words, to unveil that which, while legitimately part of our worldly experience, remains almost unfathomable or inexpressible through discourse – yet accessible through artistic exploration.