I.

The life cycle of a star is approximately 400 millennia, a time in which many chemical elements are formed and organized. A supernova is the end of a star’s life. That is when it stops its nuclear fusion, consuming more energy than it was capable of producing. The star shrinks in size and releases energy very quickly and thus, collapses. Although it is not possible to explain the causes of these stellar mechanisms, it is estimated that at the height of the explosion, its brightness is so intense that it can be up to 1 billion times greater than its original light. On its death, a star releases elements and debris that travel through the universe and can form planets and even new stars. In the Milky Way, about three supernovas occur per century. The death and emergence of a star are similar events because they release a very intense glow.

II.

The Sucuri [Anaconda], suú-curi, from the Tupi language “bites quickly”, is the largest snake in the world. Females are larger than males and are up to nine meters long. After copulating, the female can eat the male and live alone for the rest of her life. Anacondas are not poisonous, they kill their prey by suffocation. Its attack is fast: it bites its prey in the upper part of its body for support, while nimbly curling and squeezing it to prevent its breathing and heart movements. When it realizes that the animal is dead, the anaconda begins to devour it by the head. The elasticity of its skin and musculature and the ease of dilating the esophagus and stomach allows it to eat a prey up to three times the diameter of its own body. For six days, the snake is practically immobile, while enzymes and bacteria in its intestines work on digestion. An anaconda can go up to six months without feeding.

III.

Looking at the sky and drawing the position of the stars were fundamental habits in the lives of native peoples who inhabited places like what we currently know as the Archaeological Site of Serra da Capivara, in the state of Piauí, in the middle of the Caatinga. Cave paintings of constellations with more than 30 thousand years record the complex astronomical knowledge of these people who also observed the movements of the sun and the phases of the moon to determine the solar noon and the transformations in the local biodiversity. Observing the Southern Cruise Constellation allowed them to orient themselves geographically. Rituals, planting, harvesting, fishing, migration had their rhythms interpreted according to influences, fluctuations and cyclical unfoldings of the celestial phenomena they looked at. For many native peoples, everything that exists in the sky also exists on Earth, as an imperfect copy.

IV.

From the serpent, its trail can be seen and with such large trails, opened passages in the earth that created the world, the streams and rivers. The undulating movement of Boiúna’s body tore and modified landscapes altering the course of rivers. Its sliding has inscribed grooves in time that keep moving and moving things. The trail of a snake is a scripture of time in the world, in grains of earth, humidity, organic matter and sediments.

…

“Of the millions of creatures that live on Earth, humans are the only ones who want to know what exists beyond their immediate environment, the only ones who care about what happened before they were born and who speculate about what will happen after they are gone”[1]. Human beings are also the only creatures that alter the time of many phenomena that surround them. An understanding of the world is offered by an understanding of time in the world. Time tells beings, determines them. Time is experience, it draws rhythms. It is a strategy for fictionalizing life. It is also used as a device in situations of oppression, as an imposition on the rhythms of phenomena.

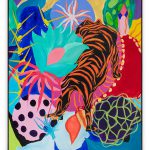

The exhibition Entre a estrela e a serpente [Between the star and the serpent] presents works that dialogue, make use of and are nourished by the different reflections about time. And these times narrated here (the end of a star, the trail of a serpent, guidelines from observations of celestial phenomena that guided life) are world stories, they are contextualization agents that bring the works together while simultaneously also differentiating them in their provocations. Situating conceptions of time between the star and the serpent is a strategy to try to glimpse some spectra of apprehension of time and the many questions that involve such perceptions. Times that the eye catches, so to speak.

It is also worth mentioning that another important trigger for the exhibition with an essayistic character, is the one that is almost immediately associated with visual symbols typical of the still-life pictorial genre: the fugacity of life, the futility of vanities, the inevitability of death, the rotting fruits, the hourglass establishing the passage and implacability of time, the anatomy of dead animals, the silent and paused life of inanimate matter, the investigation of the expressive power of everyday objects in intimate constitutions of space. These images were not necessarily translated or appropriated by the artists in the show, but rather are instances brought together.

What distinguishes these work compendiums – those related to the still-life genre and the contemporary ones – are, mainly, the contexts that surround them. If, for European productions of the 16th and 17th centuries, it was at stake to celebrate the agricultural surplus, mercantilism and cabinets of curiosities, the works presented here, produced in Brazil recently, narrate a context of “after-all”, of food insecurity, of imposing a rhythm of production that exhausts the land, of dystopia, of a world in decline, of the point of no return, of the fear of losing the world… They narrate anxiety, disorientation, the lack of a possible where there is no suffocate. Is there a horizon for humans? Or are we a brief chapter in the history of the planet, very close to its last pages? How many times have you caught yourself trying to situate certain events? Before or after the pandemic? Is 2020 a year that drags on until now? And on this, language, what has been impregnated in our bodies or from which we dare not let go, our world remains and the immensity of material things that we gather are records and indices of an environment anthropized and in agony.

Also being presented at Galeria Leme are works that update ways of making and thinking about framing, themes, compositions, and still-life motivations. Dressing black plastic fruit bodies, producing landscape portraits, writing time on the shell of an egg, counting the seconds and realizing that this is life, forging and slowing down events, inventing anatomies, thinking about time in the body, retaining time in the gesture, allying oneself with organic matter and learning from it, confronting ruin, revering the passage, the reformulation and the happening of time, wanting to be in rhythm, making the unstable rigid, painting and being space, seeing still lifes in the everyday life, change the scale of ornament and architecture, questioning architecture, writing the day-night, night-day cycles are procedures that intersect among the works of artists from different generations. Without the slightest intention of covering a temporal arc or proving a formal-conceptual affinity between the works, the exhibition Entre a estrela e a serpente proposes clashes and conversations between these gestures of invention of times that are impregnated in letters, forms and colors that flow through the scenarios and are magnetized in the contours and textures of objects. Oxalá, may the gestures of Adriano Machado, Aldemir Martins, Aline van Langendonck, Ana Amorin, Ana Elisa Egreja, Aislan Pankararu, Eleonore Koch, Felipe Seixas, Fernanda Galvão, Helio Fervenza, Heloisa, Hariadne, Ilana Tzirulnik, Julia Mendonça Gallo, Marta Jourdan, Mayana Redin, Neves Torres, Raquel Garbelotti, Regina Vater, Selva de Carvalho, Simone Moraes, Suzane Schirato, Tiago Mestre and Tiago Sant’Ana, makes us believe that looking at time redesigns things and remakes the world. We can look back, design and project ourselves for a very near future moment, full of possibles. An explosion, flights of debris in search of a new order of being, a gigantic groove designed by Boiúna that establishes other times, star-bodies inhabiting Gaia. “And what at that moment will be revealed to peoples / Will surprise everyone not for being exotic / But because it could have always been hidden / When it would have been the obvious”[2].

Galciani Neves

(April, 2022)

[1] Géza Szamosi, Tempo e espaço: as dimensões gêmeas, 1988.

[2] Trecho da canção “Um índio”, de Caetano Veloso, lançada no álbum Bicho, em 1977.